Continuing Education

Every 40 seconds, a stroke occurs in the United States. This translates to approximately 795,000 strokes annually; of these, about 25% are recurrent strokes. Although stroke has declined from the fourth to the fifth leading cause of death in this country, it remains a major cause of adult disability and significantly changes the lives of stroke survivors and their families. The need for better stroke-prevention strategies is crucial. Without them, stroke prevalence and costs are expected to rise substantially over the next two decades.Defining stroke

While the broader definition of stroke includes both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, this article focuses on ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA).- Ischemic stroke is a central nervous system (CNS) infarction accompanied by signs and symptoms of stroke persisting more than 24 hours.

- TIA conventionally is defined as signs or symptoms of a brief neurologic dysfunction that lasts less than 24 hours. However, more widespread use of brain imaging (especially magnetic resonance imaging) has shown that up to one-third of patients with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours have had a CNS infarction. This has led to a new definition of TIA as a transient neurologic dysfunction resulting from focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischemia without infarction, regardless of duration.

Primary vs. secondary stroke prevention

Primary stroke prevention refers to prevention strategies in persons with no previous history of stroke or TIA. Secondary prevention refers to treatment strategies in persons who’ve already had a stroke or TIA, with the goal of preventing a recurrence.Stroke risk factors can be modifiable or nonmodifiable. Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, race, sex, ethnicity, and a family history of stroke or TIA. Modifiable factors include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and lifestyle factors. This article focuses on modifiable risk factors.

Risk factors for both initial and recurrent stroke are similar. However, people who’ve had a stroke or TIA are at increased risk for a recurrence. Annual risk for future ischemic stroke after an initial event is approximately 3% to 4%—a significant decrease over the past two decades. The decline stems from widespread use of evidence-based secondary prevention practices, including antiplatelet therapy, effective blood pressure and hyperlipidemia management, and atrial fibrillation (AF) treatment.

Secondary stroke prevention

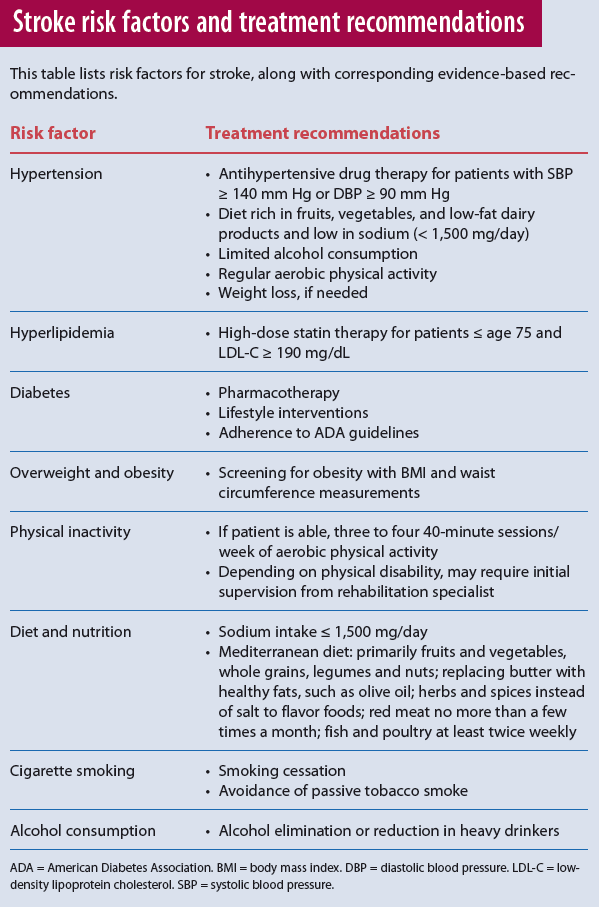

The most recent prevention guidelines for stroke and TIA place greater emphasis on lifestyle, based on the growing evidence that supports the role of lifestyle modification in vascular risk reduction. As a nurse, you can play a key role in helping stroke and TIA patients achieve evidence-based lifestyle changes. For treatment of each risk factor, see Stroke risk factors and treatment recommendations.Hypertension

Hypertension is the most significant risk factor. Approximately 70% of people with a recent stroke have a history of hypertension. Evidence shows that lowering blood pressure (BP) is effective in secondary stroke prevention. A recent meta-analysis of 10 randomized trials confirmed the benefits of lowering BP in preventing recurrent stroke. Overall, antihypertensive drug therapy was associated with a 22% reduction in stroke recurrence.Experts recommend initiating therapy in adults with a history of stroke or TIA who have a systolic BP of 140 mm Hg or higher or a diastolic BP (DBP) of 90 mm Hg or higher. No evidence suggests a specific antihypertensive medication or class of medications is best for secondary stroke prevention. Instead, the goal is to reduce BP.

Besides pharmacologic treatment, several lifestyle modifications are linked to BP reduction and should be considered as part of a comprehensive BP management plan. They include sodium restriction; weight loss, if needed; a Mediterranean-type diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products; limited alcohol consumption; and regular aerobic physical activity.

Hyperlipidemia

Epidemiologic data suggest a modest link between high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and increased risk of ischemic stroke among stroke and TIA survivors. A clinical trial that examined LDL-C lowering for secondary stroke prevention found a 2.2% absolute stroke reduction over the 5 years of follow-up in the group receiving atorvastatin (a cholesterol-lowering drug) compared to placebo. (Statin treatment carries an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, so statin drugs may need to be avoided in certain stroke survivors with a history of intracerebral hemorrhage.)Recommendations for hyperlipidemia treatment among patients with a history of stroke or TIA are consistent with the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults. High-dose statin therapy (to reduce LDL-C by 50% or more) is recommended for patients who have had atherosclerotic-related strokes, are age 75 or younger, and have an LDL-C level of 190 mg/dL or higher.

Diabetes mellitus

Both prediabetes and diabetes mellitus (DM) are common in persons who’ve had a stroke, with an estimated prevalence of 25% to 45% among stroke and TIA survivors. DM carries a higher risk for recurrent stroke. The Cardiovascular Health Study (CSH), funded by the National Institutes of Health, is a large epidemiologic observational study of cardiovascular risk factors in adults ages 65 and older living in four U.S. communities. In a substudy of participants who’d had a stroke and were followed for recurrence, those with DM were almost 1.6 times more likely to have a recurrence than those without DM.Given the high DM prevalence among stroke survivors, everyone who has had a stroke or TIA should be screened for DM. Because no studies of secondary stroke prevention have examined interventions for prediabetes or DM in preventing stroke recurrence, general recommendations are based on achieving good DM management, with lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy as the mainstays.

Studies on the optimal level of glucose control among stroke patients haven’t reported a benefit from intensive glucose lowering. Clinicians should follow recommendations from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) for glycemic control and cardiovascular risk-factor management. Also, no evidence suggests one antidiabetic agent is better than another for secondary stroke prevention; this remains an area of intensive research. ADA recommends a patient-centered approach that considers the desired glycated hemoglobin reduction, side-effect profiles, and cost.

Overweight and obesity

Defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher, obesity is linked to an increased risk of first stroke. Central obesity (large waist circumference) is more strongly associated with first stroke than general obesity.Diagnosed in approximately one-third of persons with a recent history of stroke or TIA, obesity is linked to increasing prevalence of vascular risk factors. Its association with recurrent stroke is more controversial; in fact, recent studies indicate obese patients with stroke had a somewhat lower risk for a recurrent vascular event than lean patients. This unexpected relationship is puzzling because weight loss is linked to improvements in major vascular risk factors, including dyslipidemia, DM, hypertension, and inflammation. Underestimation of the adverse effect of obesity may stem from bias in epidemiologic studies. Although weight loss benefits cardiovascular risk factors, its usefulness in secondary stroke prevention is unclear.

Despite the uncertain relationship between obesity and recurrent stroke, the most recent guidelines recommend BMI and obesity screening for all patients who’ve had TIA or strokes.

Physical inactivity

Physical activity improves stroke risk factors and may reduce stroke risk. No clinical trials have examined the effectiveness of exercise in secondary stroke prevention, but the presumed benefit is based on indirect evidence related to improved risk factors, such as BP, lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, and weight management. Two trials currently underway may provide information about the effectiveness of exercise in secondary prevention.Although the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends adults participate in three to four 40-minute sessions per week of aerobic physical activity, fewer than half of noninstitutionalized American adults achieve this goal. For stroke survivors, these recommendations may be even harder to achieve because of motor weakness, altered perception and balance, and impaired cognition. For stroke and TIA survivors who are capable of exercising, the above AHA recommendations apply. Patients with post-stroke disability should be supervised by a rehabilitation specialist at least during initiation of an exercise program.

Diet and nutrition

Several components of diet and nutrition can lead to increased BP and consequently an increased stroke risk. They include increased sodium intake, excess weight, and excess alcohol consumption. DASH-type diets (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), high in consumption of fruits and vegetables and low-fat dairy products, and reduced intake of sodium and saturated fats can help reduce BP and thus may lower stroke risk.More recently, several studies have examined the Mediterranean diet and its link to reduced stroke risk. This diet emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, poultry, fish, olive oil, and nuts while limiting sweets and red meat. A recent study found it had a significant effect on primary stroke prevention compared to a low-fat diet. Recommendations include the Mediterranean diet and counseling for stroke and TIA patients to reduce sodium intake to less than approximately 2.4 g/day, with an additional reduction to less than 1.5 g/day associated with an even greater BP reduction.

Cigarette smoking

Extensive data confirm a link between cigarette smoking and first ischemic stroke, although evidence in secondary stroke prevention is less well-established. In the CHS, elderly smokers were twice as likely as nonsmokers to have a recurrent stroke. No clinical trials have investigated smoking cessation for secondary stroke or TIA prevention. Given the overwhelming evidence on the harmful effects of smoking, such trials are unlikely to be done. All patients with stroke or TIA who are current smokers should be strongly advised to quit smoking and avoid passive tobacco smoke. Counseling, nicotine products, and oral smoking-cessation medications are recommended to support smoking cessation.Alcohol consumption

Few studies have directly evaluated the link between alcohol consumption and recurrent stroke. With ischemic stroke, the association with alcohol appears to be J-shaped, meaning that light to moderate consumption is protective whereas heavier alcohol use carries an elevated risk. The protective effect may relate to the effects of alcohol on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), whereas the elevated risk with heavier alcohol use may come from its effect on BP and glucose, as well as atrial fibrillation.Because alcohol consumption can lead to dependence and alcoholism is a significant public health problem, an important goal for secondary stroke prevention is to eliminate or reduce alcohol consumption in heavy drinkers. Light to moderate consumption (up to two drinks daily for men and up to one drink daily for women) may be reasonable, although nondrinkers shouldn’t be counseled to start drinking.

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents for secondary stroke prevention

The mainstay of secondary stroke prevention is either antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, depending on the stroke mechanism. For people who’ve had strokes or TIAs of a noncardioembolic origin, the Food and Drug Administration has approved four antiplatelet drugs for prevention of vascular events—aspirin, combination aspirin/dipyridamole, clopidogrel, and ticlopidine. Each agent carries an approximately 22% relative risk reduction for recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, or death.The drugs have important differences with direct implications for selecting a specific agent. Aspirin alone or in combination with dipyridamole is recommended as initial therapy for preventing a recurrence. Clopidogrel is recommended as a reasonable replacement for aspirin or aspirin/dipyridamole, as well as for patients with aspirin allergies. The aspirin/

clopidogrel combination isn’t recommended for routine long-term secondary prevention because of an increased hemorrhage risk. Ticlopidine rarely is used in clinical practice because of its side effect-profile and availability of newer agents.

Atrial fibrillation

AF is an important risk factor for stroke and may cause 10% to 12% of all strokes each year. Several validated risk assessment tools classify stroke risk among patients with AF, taking into account such factors as comorbid heart failure, hypertension, DM, and age. Research shows an increasing stroke risk with higher scores on the classification system (more comorbidities along with AF). The evidence is strong and consistent for using warfarin in preventing stroke among AF patients, for both primary and secondary prevention. The optimal warfarin dose for stroke prevention among these patients is one that produces an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0 to 3.0. Maintaining a therapeutic level is a challenge, though. A high percentage of AF patients have subtherapeutic levels and therefore inadequate stroke protection.Newer agents, such as apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban, also can be used for secondary stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular AF. For patients unable to take oral anticoagulants, aspirin alone is recommended. Clinicians should base selection of an agent on the patient’s risk factors and preference, drug interactions, and other clinical characteristics.

Life’s Simple 7®

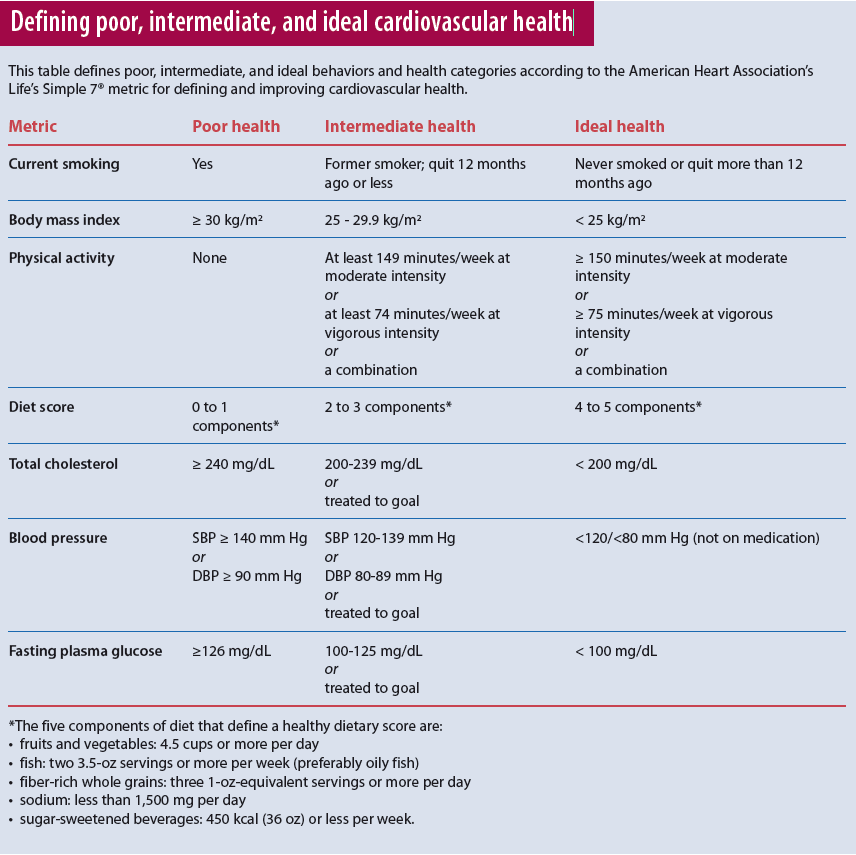

Despite our knowledge of stroke risk factors and strong evidence on treatment strategies to control risk, we’ve been largely unsuccessful in supporting good risk-factor control after stroke. Research continues to show suboptimal control of vascular risk factors in patients who’ve had strokes. The American Heart and Stroke Association’s 2020 goal is to improve Americans’ cardiovascular health by 20%. Toward this goal, these organizations have defined seven modifiable health metrics (BP, cholesterol, glucose, exercise, smoking, diet, and BMI) that increase the chance of living free of cardiovascular disease and stroke; these are called Life’s Simple 7. Although designed for primary prevention, Life’s Simple 7 metrics also apply to secondary stroke prevention.In a recent study examining Life’s Simple 7 among stroke survivors, investigators reported that fewer than one in every 100 stroke survivors met all AHA criteria for ideal cardiovascular health. (See Defining poor, intermediate, and ideal cardiovascular health.)

Implications for nurses

Clinicians need to develop effective interventions that engage stroke survivors and their families in achieving excellent risk factor control and subsequently reducing stroke burden. For nurses, a key challenge in secondary stroke prevention is providing education and supporting adherence to secondary-prevention medications and lifestyle changes. Nursing has played a significant role in quality improvement programs, such as the American Heart and Stroke Association’s “Get With the Guidelines–Stroke” program to improve initiation of secondary prevention measures in acute-care settings.As nurses, we have a responsibility to ensure secondary stroke-prevention practices across the continuum of care. Research shows that medication adherence diminishes over time, with more than one-third of patients stopping medications in the 2 years after stroke. Not only must we provide information about secondary-prevention drugs patients will take after discharge (including antiplatelets or anticoagulants, antihypertensives, and statins); but we also must assess for potential barriers to adherence. Poststroke disabilities, such as swallowing difficulties, motor weakness, and cognitive impairment, may interfere with medication management. Involving family members (especially the primary family caregiver) in discussions about medications is crucial. Also, be sure to assess the patient’s financial and insurance-related issues. If inadequate finances are a potential barrier to medication adherence, consult with a social worker to assist the patient.

Begin education early in the patient’s hospital stay and reinforce your teaching on a regular basis. Be sure to provide written materials, as stroke survivors and their families report difficulty recalling information given during the hospital stay. Post-discharge follow-up programs (by telephone or in person) to identify concerns about medications and to ensure all prescriptions have been filled can boost adherence.

Health promotion

Although health promotion is an important domain of nursing care, some nurses devote little patient-encounter time to it. The significance of lifestyle in secondary prevention and the low rate of control among stroke survivors highlights the need for action in this area.We need to use approaches that support patients in risk-factor self-management in their own environment. Lifestyle changes, such as increasing physical activity, need to be tailored to each individual, with consideration of stroke-related deficits. Interventions with stroke survivors to increase awareness of risk and manage risk factors over the long term, such as education, written materials, behavior modification, and stroke nurse specialist follow-up, have shown modest effects. Empowering patients to succeed in goal-setting around healthy lifestyle choices has proven to be an effective strategy.

Post-Stroke Checklist

The Post-Stroke Checklist was developed in 2013 by an international team of stroke experts to help ensure stroke survivors’ long-term needs are identified and managed appropriately. The tool addresses 11 areas, including secondary stroke prevention, mood, communication, relationships, and incontinence. These often-overlooked needs have a tremendous impact on quality of life and long-term outcomes after stroke. The easy-to-use checklist can be incorporated into regular follow-up care after stroke; visit http://goo.gl/0RZKT4 to see the checklist.Health information technologies

Health information technologies may hold promise for supporting self-management practices around risk- factor control—both in real time and over the long term. A Netherlands study reported modest support for improved risk-factor control through a website personalized to individual risk, identified during a baseline visit with a nurse practitioner. Patients were instructed to use the website frequently and to log in at least every other week to submit new risk-factor measurements, BP, or smoking status, as well as to read and send messages. The sample included both patients at risk for a first stroke and those at risk for a recurrent stroke. After 12 months of participation, patients in the Internet-based, nurse-led vascular prevention group showed a 14% reduction in Framingham heart risk score compared to patients in the usual care group.Evidence is building for the effectiveness of mobile health (mHealth) tools in supporting lifestyle changes. Numerous health apps can be recommended to stroke survivors to identify their risk factors and provide a risk score, including the American Heart Association’s My Life Check, which provides a score related to Life’s Simple 7. A recent study examined use of an mHealth app at the bedside; nursing students used a secondary prevention app to provide patients with information about risk factors at the bedside. Evidence-based practice has been cited as a core competency for nurses; now it’s possible to have this evidence at the bedside so nurses can more easily translate it into practice, thereby improving secondary stroke prevention and promoting better patient outcomes.

The global trend of increasing stroke incidence underscores the importance of working with patients who’ve had strokes or TIA to reduce their recurrence risk. Nurses play an essential role in screening for risk factors, increasing awareness of risk, and supporting stroke or TIA survivors in reducing risk, particularly when it comes to adhering to medications and lifestyle changes. The complexity of behavior change required suggests multifaceted and tailored strategies most likely are needed to support and sustain change.

Carole L. White is an associate professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio.

Selected references

American Heart Association. My Life Check – Life’s Simple 7. heart.org/HEARTORG/

Conditions/My-Life-Check—Lifes-Simple-7_UCM_471453_Article.jsp

Brenner DA, Zweifler RM, Gomez CR, et al. Awareness, treatment, and control of vascular risk factors among stroke survivors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19(4):311-20.

Bushnell CD, Olson DM, Zhao X, et al. Secondary preventive medication persistence and adherence 1 year after stroke. Neurology. 2011;77(12):1182-90.

Crossman T, Rider T. Novel oral anticoagulants. InnovAiT. 2013;6(8):535-7.

FitzGerald LZ, Rorie A, Salem BE. Improving secondary prevention screening in clinical encounters using mHealth among prelicensure master’s entry clinical nursing students. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2015;12(2):79-87.

Kaplan RC, Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT, et al. Vascular events, mortality, and preventive therapy following ischemic stroke in the elderly. Neurology. 2005;65:835-42.

Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/

American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-236.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarth D, et al; American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task Forces and Statistics Committee. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613.

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29-e322.

Philp I, Brainin M, Walker MF, et al. Development of a poststroke checklist to standardize follow-up care for stroke survivors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22(7):e173-e180.

Vernooij JW, Kaasjager HA, van der Graaf Y, et al; SMARTStudy Group. Internet based vascular risk factor management for patients with clinically manifest vascular disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344: e3750.

Wei J, Hollin I, Kachnowski S. A review of the use of mobile phone text messaging in clinical and healthy behaviour interventions. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(1):41-8.